Please Note: We have listed this article / course as a SCROLLABLE TEXT VERSION in OVERVIEW TAB and FLIPBOOK in the MATERIAL TAB on this page for those interested in auditing the material. If you are needing Continuing Education (CE) or a certificate of completion, please enroll in the course or get a Platinum membership and access all our courses at your leisure. Enrolled students must take and pass the short quiz to earn CE credits. In addition, this course needs to be self-reported. Self-reporting information will be accessible once you complete the quiz.

You might not think it likely, but the design of the built world is closely tied to racial equity. Racism in America is a deeply complex issue that has existed since the country began. To understand how design impacts racial equity, we must first understand how systematic racism has impacted people of color throughout our history. This article The Role of Design in Racial Equity: How the Built Environment Impacts Issues of Race takes a deep dive into the ways that design and racism have closely intermingled over time. We also take a hopeful look into more recent designs that aim to improve social equity rather than detract from it. Although our history shows centuries of oppression that has disadvantaged people of color, the future will not look this way. With helpful resources like the AIA Blueprint, developers and architects alike are actively creating an equitable future for all.

What you will learn

- Understand how systematic racism has impacted people of color throughout our history

- Explore the relationship between racial inequity and the built environment, encompassing issues from displacement to the structural aspects of buildings themselves

- Understand the influence of racism on housing through redlining, which involved the government assessing lending risk based on neighborhood racial composition

- Gain an understanding of how designing with racial equity in mind ensures universal access to clean water, air, housing, and public spaces for all communities

Discover Sustainability Education Tailored to Your Preferences in two convenient formats:

SCROLLABLE TEXT VERSION in OVERVIEW TAB

For those who appreciate a clean, scrollable format for easy reading, our text version is the ideal choice. This user-friendly format lets you delve into our sustainability articles at your own speed.

FLIPBOOK in MATERIAL TAB

To explore the interactive flipbook version, visit the ‘MATERIAL‘ tab for a dynamic reading experience. Choose the format that suits your preference and navigate through valuable sustainability content. Please be advised: To qualify for CE credits, complete the accompanying quiz located under the ‘Course Content’.

THE ROLE OF DESIGN IN

RACIAL EQUITY

HOW THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT IMPACTS ISSUES OF RACE

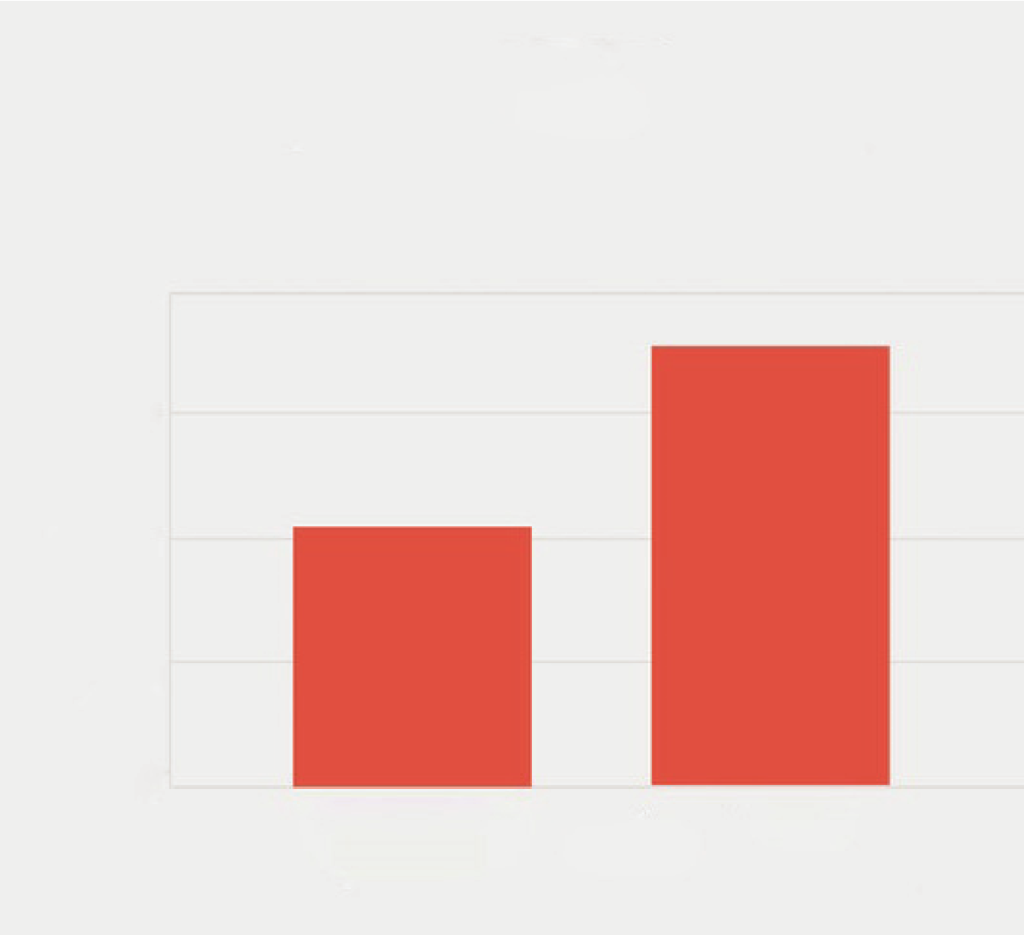

Race is an incredibly complex topic, both in America and around the world. It has played a role in every aspect of civilization – including housing and building design. Black homeownership sits around 42%, Latinos 48%, and Native Americans 51%, meanwhile white homeownership hovers around 73%. (USAFacts, 2020) A long history of oppression has created a system in which people of color experience extreme disadvantages. The issue stretches far beyond housing into health, life expectancy, education, and more. In this article, we’ll take a deep dive into the events leading up to this point and how architects, design professionals, and developers can create a better, more racially equitable future.

WHAT IS RACIAL EQUITY?

Racial equity refers to the process of eliminating racial disparities by changing practices, policies, systems, and structures. This is an ongoing, intentional process of prioritizing the creation of measurable change in the lives of people of color which, in turn, improves the outcomes for everyone. As we reach big milestones in racial equity, we move closer to racial justice, in which all people of color have the resources, power, dignity, and self-determination to thrive. Glenn Harris, president of Race Forward, puts it best, “Racial equity is about applying justice and a little bit of common sense to a system that’s been out of balance. When a system is out of balance, people of color feel the impacts most acutely, but to be clear, an imbalance system makes us all pay.” (What is racial equity? 2021)

Racial equity refers to the process of eliminating racial disparities by changing practices, policies, systems, and structures

It’s also important to make the distinction between racial equity and equality. While equality provides the same resources to everyone, it does not account for the fact that we all come from different situations that lead to us each having different outcomes. (What is racial equity? 2021) For example, the American government delivered stimulus checks to many of its citizens during the pandemic. While this was an equal amount of money for all, it wasn’t equitable because each person has different circumstances. Many people of color face systematic oppression that has forced them into a lower economic class than their white counterparts. For some people, the stimulus check was “free money” that they could use to make an extravagant purchase. For others, it was much-needed relief to pay the bills for the month. Although the funds were equal, they weren’t equitable – everyone did not have the same outcome.

HOW DOES RACIAL EQUITY RELATE TO THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT?

People of color, and especially Black people, have faced racism in America since the country was formed and founded in the 1700s. In fact, it is the racism of the generations before us that formed what we now call systematic racism. That is, the complex interaction of structures and systems our modern world is built on that disadvantage African Americans and other people of color. It is the very culture that we live in and extends into governmental policies and institutions. The impacts of systematic racism can be seen in every facet of life – education, health care, employment criminal justice, politics, and housing. (Yancey-Bragg, 2020) There are many ways that racial inequity relates to the built world – from displacement to the buildings themselves. The first example of racial inequity and housing can be seen in America’s treatment of Native American communities. The Indian Removal Act of 1830 allowed the federal government to force Native Americans to relocate in the southeast so that white people could settle their land. Land that Native Americans lived on, in their own structures, for centuries. This resulted in the Trail of Tears – a two-decade-long forcible march leading the Native Americans west of the Mississippi River, wherein thousands died of disease, exhaustion, and hunger.

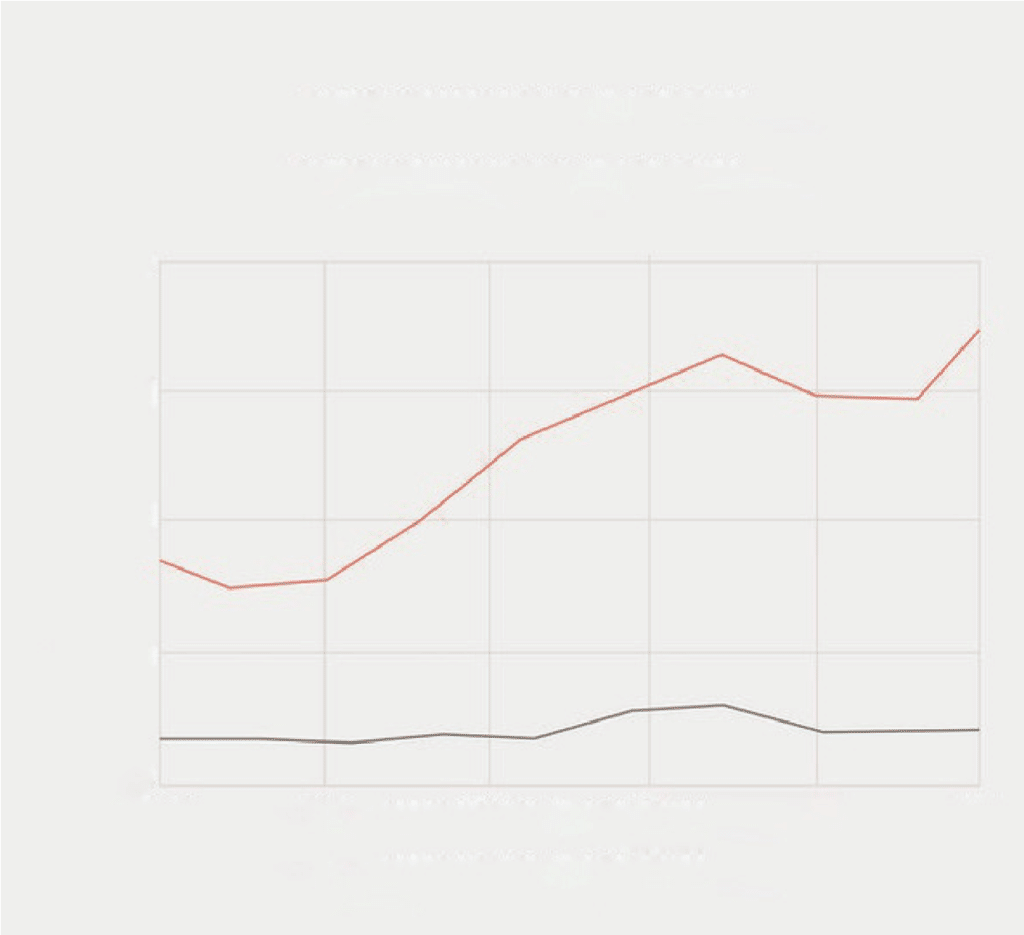

In 1887, the Dawes Act forced communal tribal lands to convert into individually-owned lots, then gave two-thirds of that land to white people. The government encouraged the Native Americans who did still hold land to pursue white American lifestyles, like farming. Native Americans lost 90 million acres of land and saw their traditions slowly die off as thousands of families were displaced. This unfair treatment has continued on, well into modern times. Today, 22% of Alaska Natives and American Indian people live in poverty, compared to just 8% of white people. Centuries of displacement and housing insecurity have led to financial insecurity. American Indians and Alaska Native people are less likely to own homes. The value of white people’s homes is also almost double, on average, than the value of Native American homes. (Solomon et al., 2022) We can also see how racism impacts housing in redlining, which refers to when the US government assessed the risk of lending home loans to people based on the racial composition of each neighborhood. Neighborhoods that were predominantly of color, often mostly Black or Latino, were considered riskier and banks could use the government’s guidelines to deny them mortgages. This also perpetuated the idea that people of color are not only a danger financially but also a threat to property values. From 1934 to 1962, only 2% of Federal Housing Association (FHA) loans were given to nonwhite families. The effects of redlining can still be seen today – 74% of the neighborhoods that were considered risky are still majority nonwhite and low to moderate-income. Redlining made it almost impossible for people of color to purchase their own homes. (Solomon et al., 2022) Even still, people of color also face displacement from the neighborhoods that are historically ethnic thanks to gentrification. In short, people move to urban areas for access to jobs, historical areas, better public transportation, and more affordable housing.

Real estate developers are moving into these areas as well, renovating old buildings and turning a huge profit by selling at a much higher price or increasing rent. As a result, people who have lived in these areas for decades and even generations are forced out by the increasing cost of living and property taxes, as well as a change to the community culture. You can learn more about gentrification in our article “Gentrification vs Revitalization: How We Can Create Social Equity Through Responsible Real Estate Development” on the GBRI and USGBC education platforms. Although redlining has since been outlawed and replaced by laws meant to make loans more accessible to all, these issues persist today. Redlining systematically kept people of color, especially Black and Latino people, in a state of financial stagnation. Without the option to own property, it becomes extremely hard to save and survive as a family, much less build generational wealth to pass down to future children. Redlining, along with gentrification, has pushed Black communities into more industrial areas that naturally have extremely limited access to public transportation, schools, grocery stores, and public spaces. (Improving racial equity through Greener Design 2021)

There are many ways that racial inequity relates to the built world - from displacement to the buildings themselves.

We can also see how racism impacts housing in redlining, which refers to when the US government assessed the risk of lending home loans to people based on the racial composition of each neighborhood

WHAT’S AT STAKE?

Issues of systematic racism have culminated in our current situation. In 2018, the National Center for Environmental Assessment at the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) found that Black Americans are 1.54 times more likely than white people to live near polluting facilities. That means that Black people are more likely to breathe dirtier air and develop health problems, like lung and heart disease. In a 2017 Baltimore City Health Department report, it was found that Black and white neighborhoods have close to a 20- year gap in life expectancy. Similar disparities can be seen in other major cities, like Chicago and Philadelphia. (Improving racial equity through Greener Design 2021) As if lacking access to education, transportation, public spaces, and affordable homes wasn’t enough, systematic racism has caused people of color to also experience housingrelated health issues. Clearly, poverty and health are closely tied together.

When you consider that the median net worth of Black families in the US is $17,150 while the median net worth of white families is $171,000, you can see how great the disparity is. (Improving racial equity through Greener Design 2021) It’s also worth noting that this wealth disparity translates into a lack of health insurance.

In 2018, the National Center for Environmental Assessment at the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) found that Black Americans are 1.54 times more likely than white people to live near polluting facilities

On average, American families spend $8,200 on health care premiums which would be about 20% of the average household income for Black families. Remember, these families are also more likely to need much of that income for rent, unlike many white families who own their homes. Black people are also almost two times more likely to be uninsured – 9.7% of African Americans were uninsured in 2018, compared to 5.4% of white people. (Taylor, 2019) If Black people had better access to funding to purchase homes, they would likely be able to save more money, build wealth, and afford health care. As mentioned earlier, people of color tend to be pushed into more industrialized areas. These areas, which are often not planned or built to support entire communities of people, lack reasonable access to healthy food. Since the 1990s, a link between food availability and poverty has been clearly proven in research. The fact remains that in poor areas, supermarkets and farmers’ markets with fresh food are harder to come by. It’s easier and often cheaper to grab processed food from a fast-food restaurant or gas station. More recent research, however, shows that Black and Hispanic neighborhoods have more small grocery stores that lack fresh food than large supermarkets when compared to white neighborhoods with similar poverty rates.

(Brooks, 2014) These areas are often referred to as food deserts – geographic areas in which residents have little to no access to affordable healthy food. There is some argument about what to call this issue. Some researchers note that food deserts imply that an area has no potential to flourish and could breed acceptance instead of action. Some prefer the term food mirage, swamp, or apartheid. (Sevilla, 2021) Whatever we call it, the lack of fresh food in neighborhoods of color is, at its heart, an issue of design. It is the lack of well-planned neighborhoods that also adds to health issues for people of color.

In a 2017 Baltimore City Health Department report, it was found that Black and white neighborhoods have close to a 20-year gap in life expectancy.

When you consider that the median net worth of Black families in the US is $17,150 while the median net worth of white families is $171,000, you can see how great the disparity is

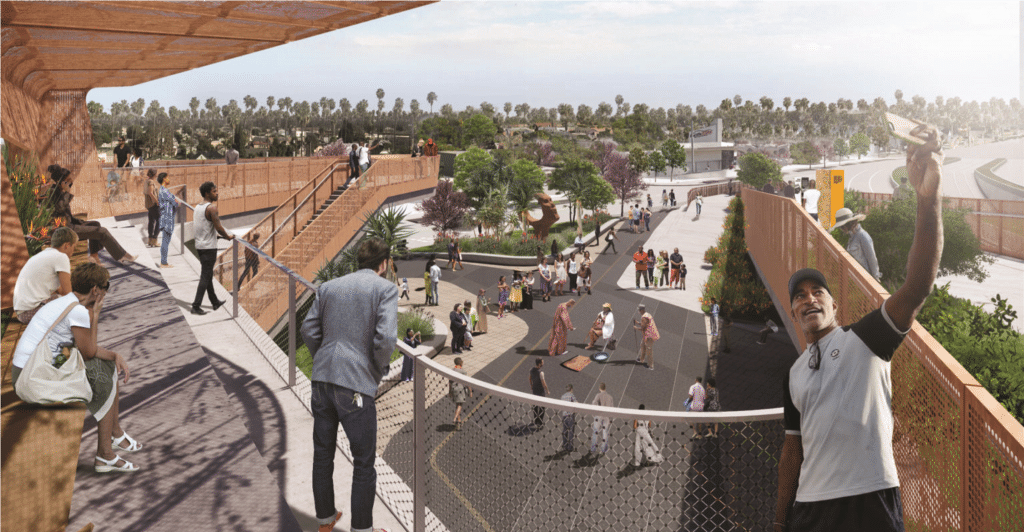

THE I AM PARK, LOCATED AT SLAUSON AVENUE, WILL CELEBRATE RESOURCEFULNESS AS THE POSITIVE OUTCOME OF STRUGGLE.

MOVING TOWARD MORE RESPONSIBLE DESIGN

Designing with racial equity in mind would mean that people of all communities have access to clean water, air, housing, and public spaces. It would also mean that communities have equal access to public transportation, affordable grocery stores, and more. (U.S. Climate Resilience Toolkit) Equity, in particular, tells us that funds need to go to communities of color. If you take a look at predominantly white communities, you can see that they already have access to these basic human rights. Funds must first be used to get all communities on a level playing field before exploring other aspects of infrastructure. It’s worth noting that we face a unique problem today. We’re building in cities that have been haphazardly planned for decades and centuries. We must now use smart growth strategies to

ensure we build resilient cities that can face future challenges related to global warming, as well as correcting racial inequities. Very few cities actually employ architects with the training to face these issues. One potential solution is to partner with local American Institute of Architects (AIA) chapters to identify a way to incorporate a City Architect initiative into the community. The AIA’s City Architect initiative is designed to help cities create strategic visions of urban design that use universal equitable design strategies. City Architects also help facilitate public space programming, connect with the community, help with planning technical details, and develop resilience requirements. Each area is unique, so having a City Architect who understands the needs of each individual city is incredibly beneficial. (21st Century city architect – blueprint for better 2019)

Designing with racial equity in mind would mean that people of all communities have access to clean water, air, housing, and public spaces

AT 54TH STREET AND CRENSHAW BOULEVARD, TWO POCKET PARKS WILL ANCHOR THE SOUTHERN CORNERS OF THE INTERSECTION AND SERVE AS THE FUTURE HOME OF THE COUNCIL DISTRICT 8 HEADQUARTERS.

We can see examples of the AIA’s work for racial equity in recent building and community design. The Crenshaw neighborhood in Los Angeles is one example. Black and JapaneseAmericans moved in in the 1970s after federal fair-lending enforcement began. For some time, it flourished as a multicultural hub within the city of Los Angeles. However, the Crenshaw/LAX light rail line and economic development threaten to increase growth that would encroach on longtime occupants of the area. The city built the light rail at-grade in Crenshaw, rather than below grade as it did almost every other major commercial area in the city. This means the light rail would have a disproportionate effect on the Black community. (Improving racial equity through Greener Design 2021) As a result, the residents banded together to envision a new future for the Crenshaw neighborhood. The vision includes a 1.3-mile park

called Destination Crenshaw that would include rotating art installations featuring Black artists along Crenshaw Boulevard. The project is still underway but shows us the importance of residents having a say in what their neighborhood needs in terms of the built world. The community sought out the help of Gabrielle Bullock, a fellow of the AIA, to aid in the process and help them overcome obstacles as they push for racial equity in Crenshaw. Similar initiatives are occurring in Houston. The Third Ward is a historically Black neighborhood, at the center of which lies Emancipation Park. The park is a 10-acre plot of land purchased by formerly enslaved people in 1872. It was purchased to celebrate the end of slavery in Texas. The Third Ward has been a bustling community since the 1930s – yet redlining, food deserts, and increasing housing costs are affecting the area, too.

The AIA’s City Architect initiative is designed to help cities create strategic visions of urban design that use universal equitable design strategies.

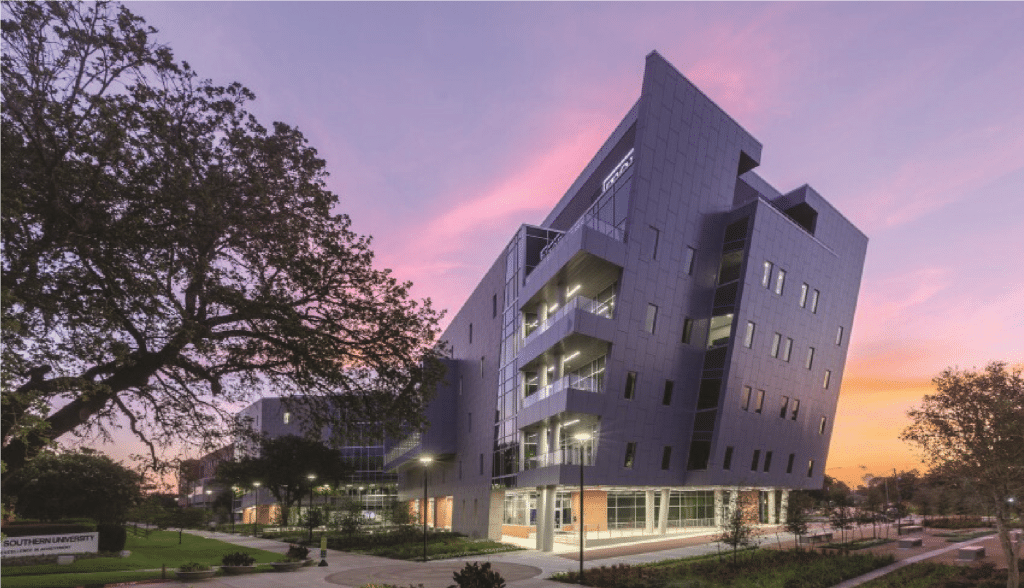

Antoine Bryant, an associate AIA member and architect at Moody Nolan, helped CEO Jonathan Moody design a cutting-edge library at Texas Southern University. The library is meant to inspire the next generation of Third Ward residents and give them the confidence and support needed for continuing the fight for racial equity. (Improving racial equity through Greener Design 2021) Bryant himself was born in public housing in Brooklyn and can attest firsthand to the unhealthy environment that his family was subject to. There were no libraries or colleges nearby – now, he’s heading up community outreach on the new library at a top historically Black university. Bryant held workshops and engaged with students, faculty, and university staff to ensure that the structure would be designed to make students and people of the broader area feel like they had an accessible space to use digital tools, read, and experience a sense of community. The library includes green features to reduce energy use. It’s close to public transit and, of course, education.

It is a great example of using design to create a racially equitable building – one that is a healthy, sustainable, and safe space that helps put people of color on a level playing field.

The library is meant to inspire the next generation of Third Ward residents and give them the confidence and support needed for continuing the fight for racial equity.

DESIGNING FOR RACIAL EQUITY

Racial equity, and the larger picture of social equity, are complicated to say the least. Systematic racism still runs rampant in society today, and the effects of redlining and nowextinct governmental policies have lingering impacts on communities of color. A lack of access to affordable housing has led to a cycle of poverty for many. Additionally, gentrification and displacement have caused people of color to be pushed out of their historical homes, often into unhealthy living conditions. What began with the Native Americans during America’s inception has continued to affect people of all races today, in various ways. The results tend to be the same: people of color are not given the same opportunity for housing, as well as health care, education, job opportunities, and more. There is a way forward. Architects, real estate developers, design professionals, and other leaders are changing the way we design, build, and rehabilitate the built space. Now more than

ever, it is imperative that we build for smart

responsible growth. Buildings must be designed

for resilience while maintaining the area’s

historical culture. Only when we create equitable

opportunities for housing and public spaces for

people of color can we truly move forward to a

better future for all.

At GBRI, as an organization and a community,

we firmly believe a truly sustainable future must

also be an equitable one where every human

is treated equally and fairly irrespective of

color, shape, gender, religion, political belief,

or nationality—and our community is a hub for

empowering all its members to learn beyond the

borders and boundaries of convention. If you

haven’t already, we welcome you home to the

GBRI community where we don’t stop

with just learning.

If you enjoyed this article,

we encourage you to check

out our climate change,

and social equity series

of articles, courses, and

meaningful exercises.

THIS PORTION OF DESTINATION CRENSHAW CREATES A NEW PUBLIC SPACE JUST SOUTH OF THE HISTORIC LEIMERT PARK

Systematic racism still runs rampant in society today, and the effects of redlining and now-extinct governmental policies have lingering impacts on communities of color.

RELATED COURSE VIDEOS

Listed here are some videos our researchers came across while researching this project. This is not part of GBRI’s course, but we encourage you to check them out along with the resources and references listed on next page.

REFERENCES:

The American Institute of Architects. (2019). 21st Century city architect – blueprint for better. The American Institute of Architects. Retrieved February 2, 2022, from http://blueprintforbetter.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/21st_Century_City_Architect_final.pdf

Brooks, K. (2014, March 10). Research shows food deserts more abundant in minority neighborhoods. The Hub. Retrieved February 2, 2022, from https://hub.jhu.edu/magazine/2014/spring/racial-food-deserts/

Improving racial equity through Greener Design. Blueprint For Better. (2021, January 7). Retrieved February 2, 2022, from https://blueprintforbetter.org/articles/improving-racial-equity-through-greener-design/

Lerner, M. (2020, July 23). One home, a lifetime of impact. The Washington Post. Retrieved February 2, 2022, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/07/23/black-homeownership-gap/

Sevilla, N. (2021, April 2). Food apartheid: Racialized access to Healthy Affordable Food. NRDC. Retrieved February 2, 2022, from https://www.nrdc.org/experts/nina-sevilla/food-apartheid-racialized-access-healthy-affordable-food

Solomon, D., Maxwell, C., & Castro, A. (2022, January 19). Systemic inequality: Displacement, exclusion, and segregation. Center for American Progress. Retrieved February 2, 2022, from https://www.americanprogress.org/article/systemic-inequality-displacement-exclusion-segregation/

Taylor, J. (2019, December 19). Racism, inequality, and health care for African Americans. The Century Foundation. Retrieved February 2, 2022, from https://tcf.org/content/report/racism-inequality-health-care-african-americans/?agreed=1

USAFacts. (2020, October 16). US homeownership rates by race. USAFacts. Retrieved February 2, 2022, from https://usafacts.org/articles/homeownership-rates-by-race/

U.S. Climate Resilience Toolkit. Social Equity | U.S. Climate Resilience Toolkit. (n.d.). Retrieved February 2, 2022, from https://toolkit.climate.gov/topics/built-environment/social-equity

What is racial equity? Race Forward. (2021, October 5). Retrieved February 2, 2022, from https://www.raceforward.org/about/what-is-racial-equity-key-concepts

Yancey-Bragg, N. (2020, June 15). What is systemic racism? here’s what it means and how you can help dismantle it. USA Today. Retrieved February 2, 2022, from https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2020/06/15/systemic-racism-what-does-mean/5343549002/